Barbara’s work

This is a selection of Barbara’s artwork; additional pieces will be added. Barbara’s creative vision extended throughout all of her day-to-day affairs and these experiences fed her vision.

From a young age, Barbara drew and painted. The artwork from her youth was compelling (and is among the pieces that will be added). Barbara studied commercial design, architecture, art history, filmmaking, sculpting and painting. Painting became the primary focus of her continuing education and remained so during the rest of her life.

The earliest paintings here are from 1987 (they’re grouped together with a few from 1988 and identified with the numbers 97, 97a, 97b, 97c, 97d, 97e, 97f and 97g). The most recent painting is probably from 2007. That was the last year Barbara painted regularly.

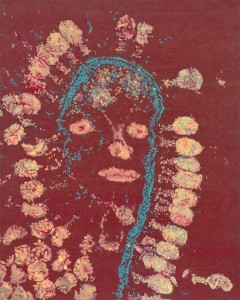

Barbara chose the subjects of her paintings for many reasons, often for their visual impact, because of an intellectual stimulus or an emotional resonance she felt when she saw them, or something ineffable that struck her about them that she could heighten and convey in a painting. One of the reasons she painted the Ebola virus (number 89) was because the innocuous, playful appearance of it when blown up under a microscope was so at odds with its deadly potential. Barbara reveled in the beauty of microscopic images and liked to note the similarity of patterns in nature at vastly different scales. Although many of her paintings may appear to be abstract, they seldom are.

Barbara was fond of creating ambiguity in her paintings, which is the one reason I know of that she didn’t want to title them (arbitrary key numbers take the place of titles on this site). She liked that different people would see different things and most often found their takes to be valid ones. She was aware of how subtle differences could be perceived, and enjoyed hearing others’ interpretations of the images in her paintings (please see her artist’s statement).

Barbara often used working titles, some were quite funny. She referred to number 88 as “deficiency,” coming from one way of looking at the image, “de fish in de sea.”

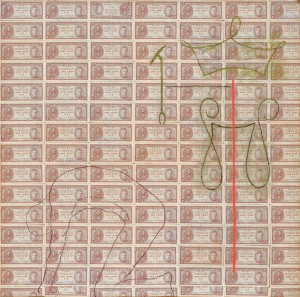

In the late ’80s Barbara began making the Rorschach paintings; aside from the paintings mentioned above, the Rorschachs are the earliest paintings here. Almost 25 years on, it’s hard to recall exactly why she chose this motif. One of the things that attracted her was their near-symmetry; another was the latent, implied images that some saw as one thing and others saw as another with almost endless potential interpretations. I think a strong attraction was that these were images that were created to be interpreted. She was aware of Andy Warhol’s Rorschachs; she hesitated for a short while, thinking about doing something so similar, but her vision and her technique were her own. She drew and painted all of these by hand, which is something a lot of people have asked about. The images generally adhere closely to the forms of the actual Rorschach series but Barbara freely changed shapes, accentuating one thing, obscuring another, frequently anthropomorphizing or creating visual double entendres. For some, she followed the original colors, on others she varied widely. Sometimes she layered them with other images, most often guns. The motif painted on the seat of a chair (number 102) resembles a Rorschach inkblot but isn’t one of the ten in the actual series. Barbara read at least two books and many articles about the Rorschach test while she was painting them.

Even while she was making the Rorschachs, she painted other subjects, including animals, people, anatomy, scenes from movies and especially microscopic blowups. These inner landscapes captured her imagination and remained central to her paintings from the mid-90s on. They were biological, often diseases, at many different magnifications. All of the same approaches and liberties she took with the Rorschachs are found in these paintings, including rigorously informing herself about the scientific facts about the images she used.

Another notable aspect of Barbara’s paintings is her use of unusual grounds for the paint, like money and pages from books. This is entirely my unsubstantiated observation, but take a look at number 10, I like the way the seals on the money make the negative space into eyes and turn the inkblot into a face.

Barbara’s paintings were included in a wonderful group show at MoMA PS1 in the summer of 2004, “Curious Crystals of Unusual Purity,” and are visible in the photos of the exhibit on their website. In late May 2014, one of her paintings (number 70) was included in a group show at Exile gallery in Berlin. Barbara brought this same painting and one other (number 5) to Berlin in 2010 to be shown in Exile’s “Lost Horizon/Head Shop” group show—this was the last exhibit she participated in.

Also included on the website are two boards and one sheet of paper with color tests. Although Barbara used these as tests for colors, layers and shapes, and didn’t plan to exhibit them, they’re surely beautiful, and beautifully rendered. One of them (number 103) hangs in our apartment, as it has for the past several years. One day in her studio I asked her to stop where she was and give it to me, which she did. I was lucky to have had that kind of relationship with her. We were a couple and lived together for the last 25 years of her too-short life.

Don Deering, November 2015